- Home

- Bob Thompson

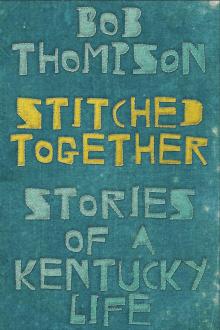

Stitched Together

Stitched Together Read online

Stitched Together

Stitched Together

Stories of a Kentucky Life

Bob Thompson

Foreword by Lee Pennington

Due to variations in the technical specifications of different electronic reading devices, some elements of this ebook may not appear as they do in the print edition. Readers are encouraged to experiment with user settings for optimum results.

Copyright © 2019 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Thompson, Bob - author.

Title: Stitched together : stories of a Kentucky life / Bob Thompson.

Description: Lexington : University Press of Kentucky, 2019.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019022716 | ISBN 9780813178066 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780813178073 (pdf) | ISBN 9780813178080 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Thompson, Bob—Childhood and youth—Anecdotes. | Thompson, Bob—Family—Anecdotes. | Kentucky—Social life and customs—Anecdotes. | Tales—Kentucky.

Classification: LCC PS3620.H6527 A6 2019 | DDC 813/.6—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019022716

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting

the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

Member of the Association

of University Presses

Contents

Foreword by Lee Pennington

Introduction

Bunk’s Bull

Harp

Rocket Science

Motorsports

Balerman

Not Much Danger

The Entertainer

Threads

Beta Club

Ben

Rupp

Treachery

Spelling Bee

Cats

Boundaries

Hunter

Tree Climber

Catfish Throw

Jump

That’s My Dad

Running

Flagger

Searchlight

Old Fart

The Call

Traveling Lite

Going Down

Garages

Periwinkles

The Internet of Things

Teetum

Sangria

Photographs

Foreword

A Stitch in Timing

Bob Thompson is a storyteller, and I mean that in the highest and best sense of the word. Over the years I have had the privilege both to hear him and to read his stories. Not only does he do a great job both telling and writing stories, he also has the ability to incorporate elements of each genre into the other. Not an easy task. Hearing him tell is a bit like sitting in front of a fireplace reading a good story. Reading one of his stories reminds us we are not so far from that fireplace that we cannot hear his voice paint vivid pictures for us and give us a yarn of major significance.

In Stitched Together: Stories of a Kentucky Life, Bob uses his family and community background of growing up near Paducah, Kentucky, to bring together pieces of human fabric to make an incredible quilt. It is surely his quilt, but at the same time it is a universal quilt, belonging to all of us. The fabric is rich and soft and just thick enough to keep us warm on long winter nights.

I have noticed that by the time we reach the end of one of Bob’s stories, the story is bigger, deeper, and richer than we ever dreamed or expected it would be. The story has wings—it flies into our minds to stick in our memory like the sound of some distant train whistle or like some familiar odor that jars our recall of a time and place and moment we had somehow forgotten, giving us joy.

Take Granny in his introduction to the book. She is, in many ways, the grandmother we all know—a sweet, gentle lady who is concerned with those close to her, of course, but she also prepares to assist those she will never meet or see. It is here we find a great lesson, learning the importance of spaces, blank places, and areas of no sound, which are just as significant as what we perceive as real, solid, and important.

This is what actors, writers, and storytellers call timing: the space between the line and punch line. Go too quickly and the point is lost. Go too slowly and not much gets punched. Bob Thompson’s timing in his telling and in his writing is impeccable. You will see those important empty spaces in every single one of his stories.

I am reminded of something I heard about a little girl in kindergarten who was coloring in her coloring book. The teacher, looking over her shoulder, said, “Why, Janie, that’s wonderful! You haven’t gone outside the lines anywhere.”

“I know,” said Janie. “There’s nothing out there to color.”

Bob does not color outside the lines. His stories are accurate. He colors what’s there.

So get ready for something very special as you read these stories. Take them slowly and give their impact time to happen. Read each story and then think about it for a while. Every stitch counts; every space, empty or full, is important.

Lee Pennington

Introduction

Life’s treasures are a patchwork of stories with characters revealed in the pauses between stitches and words.

Granny sewed her life’s energy into stacks of quilts and Mom poured her love into volumes of diaries, scrapbooks, and photo albums. Their spirits speak from the cadence and rhythm between their offerings, leaving us to fill the spaces.

Mom

Mom’s diaries began in 1940, the year she became a teen and her family moved twenty miles, from Markham Avenue in Paducah, Kentucky, to the back room living quarters of a country grocery in Ragland, and the daily journaling didn’t stop until she was in her eighties, when she started forgetting.

Her entries were usually limited to a few sparse sentences with a reporter’s neutral point of view, as in this note from February 5, 1943, describing her day and a sleepover with her best friend: “Went to school, had a pep meeting, came home and went to a ball game at Tilghman. Robbie stayed all night with me.”

She wrote about little things but seemed to neglect the big things, things that were obvious to her, but not so much to later readers. At the beginning of December 1949, she knew she was pregnant, but not once in the next nine months did she write that in her diary; in August I popped miraculously into the world and her diary, heralded only by vague clues.

She showed the same neglect in her large collection of neatly typed three-by-five-inch recipe cards. I was reminded of those omissions when recently my son surprised me with a birthday book titled “Nanny’s Recipes.” Each page was dedicated to a cherished dessert of his childhood and contained a different picture of Mom, a scan of one of her recipe cards, and a short reflection of its impact on his youth. I could have guessed the first recipe: it was his favorite, “Banana Pudding,” and was always on the table when we visited my parents in Paducah or in their car when

they came to our home in Louisville. As I read his caption beneath her picture and looked at the 1940s recipe card, I busted out laughing; there was no doubt that this was the same stained recipe card Mom had used to make her first dessert as a married woman.

A week or so after Mom and Dad’s wedding, when the nightly dinners at friends’ and relatives’ houses had tapered off, Mom finally was able to show off her culinary skills to her new husband. From watching her throughout my life, I can imagine her doing ten things at once, nervously working off the recipe cards laid on the counter.

Her diary doesn’t say what the main course was, but for dessert, she made my dad’s favorite, “Banana Pudding.” The meal was already an impressive homemaking success when Mom revealed her big surprise. Digging into the perfectly browned meringue, she piled big dollops of the golden pudding onto his plate. Watching closely at his first bite, anxious for his reaction to her masterpiece, she asked, “Well, what do you think”?

With all the caution of a new husband, knowing much was in the balance, he carefully took another bite before answering. “Well,” he said finally, “It’s really good.” She let out a breath of relief. “In fact,” he went on, “The only way it could have been any better is if you’d put bananas in it.”

Snapping her head around, she saw the bananas still lying on the counter.

Mom’s recipe cards for “Strawberry Pie,” “Cherry Pie,” and “Banana Pudding” all neglected to list the obvious main ingredient. As a recipe writer, those things were obvious to her, but as a nervous cook, not so much!

Mom not only logged daily news items into her journals but continually reviewed her archives, mining diaries and picture albums to generate lists of common themes, groupings of things with a place in her heart. She left a complete list of every baby toy, its donor acknowledged and its image preserved with surprisingly talented pencil drawings. She had thick binders dedicated to pets, glassware, vehicles, jewelry, furniture, churches, cemeteries, obituaries, anniversaries, birthdays, friends, families, and me.

Her compiled record of my birth started with a short list of statistics presented without editorializing: date, time, location, weight, length, and full name, before jumping ten years ahead and giving a rare glimpse into what was important to her: “Was saved and joined Newton Creek Baptist Church, Sept. 25th, 1960. Baptized in Mr. G. S. Smith’s pond. Reverend Foster Howard was Pastor.”

After my name had been safely written in the Baptist entry roles of heaven, she returned to lesser items, including the date of my first tooth, complete sentence, caught fish, eyeglasses, spelling bee, hay-hauling, motorcycle, car, car wreck, traffic ticket, school trip, mustache, date, girl-brought-home, enema, and airplane flight. Most things bring back pleasant memories; the exceptions are the reminder of that (hilarious only in retrospect) assisted enema on the floor of our small bathroom, and her studious recording of my 1972 fall semester grade in Elements of Heat Transfer at the University of Kentucky.

Granny

I’d never thought about having blank spaces in my life until, looking through the scores of family photo albums lovingly compiled by my mother, I realized not a single section had been filled by the personal memory of a grandfather or great-grandfather. Those spaces would have to be defined through the memories of others, by a full complement of grandmothers and great-grandmothers, and by my closest childhood companions, accidental shamans who daily convened at Granny’s country grocery.

I had Maw Brim, Momma Thompson, Grandma Starks, Miss Celee (Cecilia), and Grandma, but Mom’s mother, Granny, was the constant of my childhood

Roy Parker, Granny’s handsome entrepreneurial husband and the only male progenitor alive at my birth, was taken by one of the Ohio River’s nearly annual February rages in my nineteenth month. Granny held on to his memory and the country grocery store they had built together, and I grew up next door in one of the houses she built with the insurance money.

The old farmers and returned-home-pensioners from northern factories who inhabited the repurposed church pews around the potbellied stove in the winter, and the surplus construction-site bench on the front porch in the summers, filled the empty spaces of missing grandfathers. From them I learned local lore: floods, droughts, bad crops, big snows, shootings, and youthful exploits as well as national and world history. Through their eyes, I came to know Detroit factories, world wars, depressions, deaths, arthritis, and other indignities of growing old. Just as with real grandfathers, Granny often had to clean up behind them.

Mr. Gregory Wilson had a well-known knack for colorfully punctuating his dialogue, but out of respect for Granny, he confined his best adjectives to when she was not in earshot, an exception he neglected for me. I didn’t initially notice the dichotomy between his summertime front porch talk and his winter dialogue around the Warm Morning stove. It all seemed so normal that I made no comment about it, until one afternoon when I was about four.

It was a frigid day and the regulars were gathered around the big coal stove at the back of the store, sipping nickel soft drinks from glass bottles and reminiscing about similar raw days of years gone by. Not much interested, I asked Granny if I could have a Coke. She nodded. At the front of the store I fished a bottle from the cold water of the drink box and went through the muscle-memory motions of inserting the bottle neck into the opener mounted on the front of the cooler (this was long before the era of twist-off caps) and pushing down to remove the cap. I felt the metal cap bend and heard the soft hiss of carbonation released from the bottle. Had I been more attentive, I would have noticed the absent sound of the cap joining its brethren at the bottom of the collection bin, but I paid no attention to the bottle as I went back down the candy aisle and returned to my perch on the store counter. I raised the bottle to my lips. Instead of the refreshing fizzle of cold liquid in my mouth I had expected, I felt the sharp metallic edges of the bent but still-attached cap. As this was the first such occurrence in my young life, I thought it significant enough to warrant interrupting the grown-up conversation to share the humor of the moment. Holding the bottle out as evidence, I said loudly, “Look at this! The son-of-a-bitch cap didn’t come off.”

Evidently this was a bigger deal than I’d expected because every head in the august group simultaneously snapped in my direction and all conversation stopped. “What did you say?” Granny asked, her mouth slightly opened, her head tilted to the side, and one eyebrow arched.

Everyone was looking at me, except Mr. Wilson. He seemed to be interested in something on the floor.

Sensing that I had stumbled on something significant and further comment was expected, I added, “Look, the damn cap stayed on the bottle.”

This additional commentary brought all eyebrows up in wide-eyed understanding, except for Mr. Wilson again, who seemed to go into deeper thought as he rested his face in his hands.

Granny said she had something to show Mr. Wilson up at the front of the store.

After their talk, Granny came back alone and later, when the store had emptied, she explained: there might be a time and place when I would need to use “grown-up” words to accentuate a point, but at my age and in front of customers, a recalcitrant bottle cap did not meet any of those conditions.

Mr. Wilson evidently got the message too, exercising far more caution when choosing the time and place for his renowned expletives.

Granny’s strong sense of proper timing seemed to be in touch with my mastery of the various subjects of life.

A few years later, during the usual parting fellowship in the churchyard after Sunday morning services, I was standing beside Granny as the preacher purposefully approached. Looking down at me fondly, he placed his hand on my shoulder and expressed to the surrounding family how proud he was to have witnessed me putting $2 of what he took to be my own money into the offering plate as it passed.

Not sure how to respond, the rest of the family hesitated for a moment before I spoke up. “Thank you, Reverend. I figured that since the Lord had put h

is hand on me last week when I drew that inside straight, he was due his cut of the pot.”

Granny figured it was time we stopped playing cards at the little table up by the drink box, and checkers came to be the game of choice. Nobody seemed willing to put money on checker games and my loose-lipped, ill-timed revelation postponed my further poker education till college.

Her wooden quilting frame was a permanent fixture in the back of the store. Granny used her time between restocking shelves, fixing sandwiches, and selling groceries to make dozens of quilts. She would cut pieces of colored cloth, some with previously embroidered patterns, carefully choosing the right placement for each block, and sew them together, making Dutch dolls or tulips or whatever design caught her eye in a pattern catalogue. Later, she would sew these appliqués to larger pieces to be used for the quilt, sometimes with her old treadle Singer sewing machine, sometimes by hand.

Considerable time was spent comparing before choosing the material and color for the strips to go between the blocks. She used the same material for the backing and border of the quilt. When all the pieces were ready, she’d spread the backing over the quilting frame and then stretch the cotton interlining tightly over it. Sometimes she would use thin blankets for interlining, explaining that over time they wouldn’t bunch up like cotton. Fitting a top over the interlining and making sure all the seams lined up, she would start basting them all together. Finally, she would spend weeks or months hand stitching all the layers together.

Once I asked her, didn’t she think she had enough quilts? Without looking up or missing a stitch, she smiled and explained that she might never see her great-grandchildren, but that there’d come a time when these quilts would make them feel warm and secure. She said it was the only way she could reach across time, touching and giving them her energy.

She never hurried; her stitches were small and even. Fascinated with numbers, I counted as many as eight hundred per square and did the math: sixteen thousand for a twin-bed-sized quilt! When I mentioned that some of Great-Grandmother Brim’s quilts had stitches so large that you could get your big toe caught in them, Granny smiled and said, “It’s not the size of the stitches that count, it’s the spaces between them.”

Stitched Together

Stitched Together